CHAPTER IV.

DISCOVERY OF AMERICA BY THE IRISH.

IN the preceding chapter I intimated that the Irish have some claim to the honor of having discovered America before Columbus. It is a large subject, and all I am able to, do at this time is to give the particular facts and traditions, and some hints in regard to their proper interpretation. The name of St. Brendan (or Brandan, as it is sometimes written) is well known, at least it may be found in the larger cyclopedias. He was an Irish monk, famous for his voyages upon the sea to strange lands. The traditions handed down to us from the Middle Ages contain many legends in regard to him. He belongs to the sixth century after Christ, and hence to an age where fact and fiction are strangely mingled. His death is said to have occurred A. D. 577. Report has it that he went on a nine years' voyage, and visited unknown lands. These lands are described in the work "De Fortunatis Insulis," published in the eleventh century, in the Latin language, and translated into French about the year 1120. Versions of his voyages appeared also in German, English and Dutch. Popular tradition has identified the Fortunate Islands of St. Brendan with America, and given this Irish saint the credit of discovering the western continent.

According to one legend, St. Brendan, conducted by

an angel, descended to the lower world, where he witnessed the torments of the Devil and of the damned, and subsequently he came to, the Fortunate Islands, and finally he visited Paradise. At the end of the nine years he returned to Ireland, and gave an account of his adventures. The less superstitious interpreted St. Brendan's voyages as referring to existing countries, and I now hasten to declare it here as a fact that the reports concerning St. Brendan constituted one of the causes which led the Spanish and Portuguese to undertake voyages of discovery in the western ocean. Thus St. Brendan is one of the links in that chain of influences operating on the mind of the great Genoese navigator.

There is evolution in history, as well as in other things. The voyages of the Phœnicians and of the Greek Pytheas were germs that budded in the explorations of the Irish and of the Welsh, blossomed in the expeditions of the Norsemen, and culminated and bore fruit in the discovery of America by Columbus. The Phœnicians and Columbus are the two ends of the long chain of events in the opening of the new world to civilization. Columbus was a scholar, who studied industriously all books and manuscripts that contained any information about voyages and discoveries. His searching mind sought out the writings of Adam of Bremen and the works relating to St. Brendan. It is in this wise that we are able to explain the firm conviction that Columbus invariably expressed in his reference to land in the west. In that way we are able to account for the absolute certainty and singular firmness with which he talked of land across the

ocean, and thus, too, we can account for his accurate knowledge of the breadth of the ocean.

It is now my privilege to call the attention of my readers once more to the Icelandic sagas, and show from them corroborations of the above theory concerning the discovery of America by the Irish. There was a powerful chieftain in Iceland, by name Are Marson, and the sagas tell us that in the year 983, that is, three years before Vinland was seen by Bjarne Herjulfson, he was driven to Great Ireland by storms, and was there baptized. The first author of this account was his contemporary, Rafn, surnamed the Limerick Trader, he having long resided in Limerick, Ireland. The illustrious Icelandic sagaman, Are the Wise, descendant in the fourth degree from Are Marson, states on this subject that his uncle, Thorkel Gellerson (whose testimony he on another occasion declares to be worthy of all credit), had been informed by Icelanders, who had their information from Thorfin Sigurdson, Earl of Orkney, that Are Marson had been recognized in Great Ireland, and could not get away from there, but was held there in great respect. This statement, therefore, shows that in those times (about the year 983) there was an occasional intercourse between the western part of Europe, that is to, say, the Orkneys and Ireland, and the Great Ireland or Whitemen's Land of America. The sagas from which we get our information about Leif Erikson expressly state that Great Ireland lies to the west in the sea, near Vinland the Good, six days' sail west from Ireland. Doubtless; the "VI" has arisen through some mistake or carelessness

of the transcriber of the original manuscript, which is now lost, and was erroneously written for XX, or XI, or perhaps XVI, which would correspond with the distance. Such a mistake might easily have been caused by a blot or defect in the manuscript.

It must have been in this same Great Ireland that Bjorn Asbrandson, surnamed the Champion of Breidavik, spent the latter part of his life. He had been adopted into the celebrated band of Jormsborg warriors, under Palnatoke. His relations with Thurid of Froda, in Iceland, a sister of the powerful official Snorre, drew upon him the enmity and persecution of the latter, in consequence of which he found himself obliged to quit Iceland forever, and in 999 he set sail with a northeast wind.

And now comes the most interesting part of this story. Gudleif Gudlaugson, the ancestor of the celebrated historian, Snorre Sturlason, had made a trading voyage to Dublin, in Ireland, but when he left that place again, with the intention of sailing around Ireland and returning to Iceland, he met with long-continued northeasterly winds, which drove him far to the southwest in the ocean, and late in the summer he and his company came at last to an extensive country, but they knew not what land it was. They went on shore, whereupon a crowd of the natives, several hundred in number, came against them and laid hands on them and bound them. They did not know to what race these people belonged, but it seemed to. them that their language resembled Irish. The natives now took counsel whether they should kill

the strangers or make slaves of them. While they were deliberating, a large company approached, displaying a banner, close to which rode a man of distinguished appearance, who was far advanced in years and had gray hair. The matter under deliberation was referred to his decision, when to their astonishment it was discovered that he was none other than the above named Bjorn Asbrandson. He caused Gudleif to be brought before him, and addressing him in Icelandic, asked him whence he came. On Gudleif's reply that he was an Icelander, Bjorn made many inquiries about his acquaintances in Iceland, and particularly about his beloved Thurid of Froda and her son, Kjartan, supposed to be his own son, and who at that time was the proprietor of the estate of Froda. In the meantime, the natives becoming impatient and demanding a decision, Bjorn selected twelve of his company as counselors, and took them aside with him, and some time afterward he went toward Gudleif and his companions, and told them that the natives had left the matter to his decision. He thereupon gave them their liberty, and advised them, although the summer was then far advanced, to depart immediately, because the natives were not to be depended upon and were difficult to deal with, and, moreover, conceived that an infringement on their laws had been committed to their disadvantage. He gave them a gold ring for Thurid and a sword for Kjartan, and told them to charge his friends and relations not to come over to him, as he had now become old and might daily expect that old age would get the better of him; that the country was large, having

but few harbors, and that strangers must everywhere expect a hostile reception. Gudleif and his company accordingly set sail again, and found their way back to Dublin, where they spent the winter; but the next summer they repaired to Iceland and delivered the presents, and everybody was convinced that it was really Bjorn Asbrandson, the Champion of Breidavik, that they had met with in this far-off country.

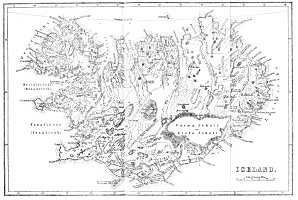

The date of Gudleif's voyage is the year 1029, and my readers may easily find the account in chapter 64 of the Eyrbyggja Saga. The portion of America here referred to is supposed to be situated south of the Chesapeake Bay, and includes North and South Carolina, Georgia and East Florida. In the saga of Thorfin Karlsefni, chapter 13, it is distinctly called "Irland-it-Milka;" that is, Great Ireland. The presumption is that the name Great Ireland arose from the fact that the inhabitants seemed to Gudlaugson's party to speak Irish; that the country presumably had been colonized by the Irish long before Gudlaugson's visit, and that they, coming from their own green island to a vast continent possessing many of the fertile qualities of their own native soil, found such an appellation natural and appropriate. I see nothing improbable in this conclusion; for the Irish, who visited and inhabited Iceland toward the close of the eighth century, to accomplish which they had to traverse a stormy ocean to the extent of eight hundred miles; who as early as 725 were found upon the Fareys (voyages between Ireland and Iceland in the tenth century were of ordinary occurrence)--a people so familiar

MAP OF ICELAND "> MAP OF ICELAND |

with the sea were certainly capable of making a voyage across the Atlantic Ocean.

The geography of the western world, according to the old Norsemen, consisted of (1) Helluland (Newfoundland), (2) Markland (Nova Scotia), (3) Vinland (Massachusetts or some part of New England), and then (4) stretching far to the south of Vinland lay Whitemen's Land or Great Ireland.

0 comments:

Post a Comment